Analysis

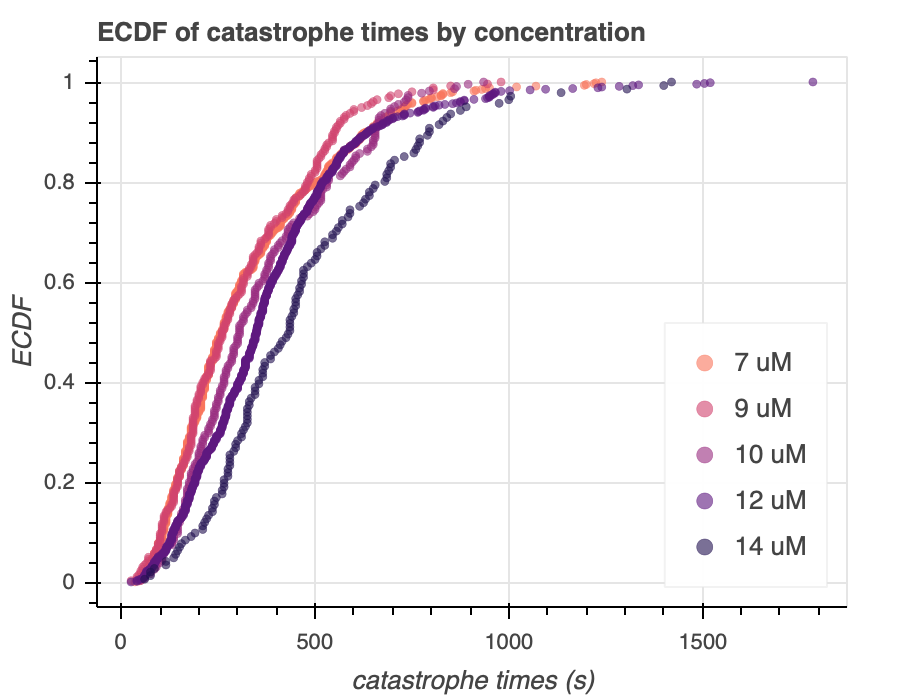

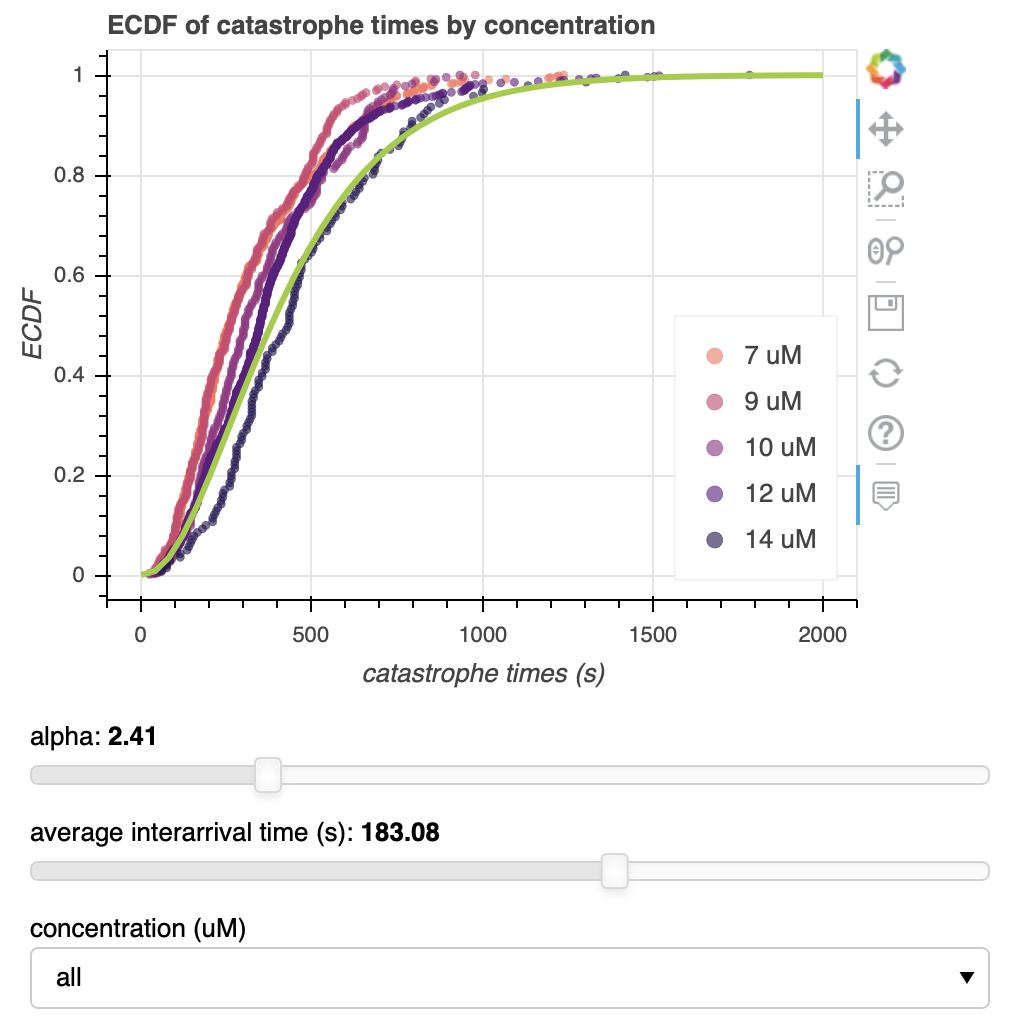

Now, we get to the heart of our analysis. We will compare the gamma distribution model to the two event distribution model in modeling catastrophe times, and we will examine how different concentrations of tubulin affect catastrophe times. In the past two sections, we used the first dataset, and now we move on to the second dataset, which contains catastrophe times for five different tubulin concentrations––$7\mu M$, $9\mu M$, $10\mu M$, $12\mu M$, and $14\mu M$. Let's first do some exploratory data analysis, and we start with an ECDF plot, as seen in Figure 4a. All Figure 4 plots were generated using the viz_explore_concentration_dataset script.

We see that for higher concentrations, the time to catastrophe increases, and this is pretty consistent as we increase the concentration. This trend is especially noticeable for smaller catastrophe times, especially below the $60^{th}$ percentile. This increase might be explained by a shift in equilibrium dynamics as the concentration increases. For microtubule formation, increased tubulin availability will drive microtubule formation in order to use up free tubulin, thus shifting the equilibrium toward the right; for microtubule catastrophe, more free tubulin will create pressure against creating more free tubulin, which may slow down catastrophe times. Interestingly, this trend is harder to see at longer catastrophe times. It is conceivable that some arrivals will take a very long time, which is within the realm of Poisson arrival processes. These long arrivals can happen at any concentration level, thus obfuscating the trend at longer catastrophe times.

Zooming in on the graphs of individual concentrations, we can also see that there are inflection points for each concentration. This is comforting, since both the gamma model and two-event story have inflection points. Interestingly, the distributions for $9\mu M$ and $10\mu M$ have noticeable bimodal distributions. This may be problematic since neither our two-story nor our gamma distribution are particularly bi-modal. We can further explore this dataset by looking at a strip box-plot, as seen in Figure 4b.

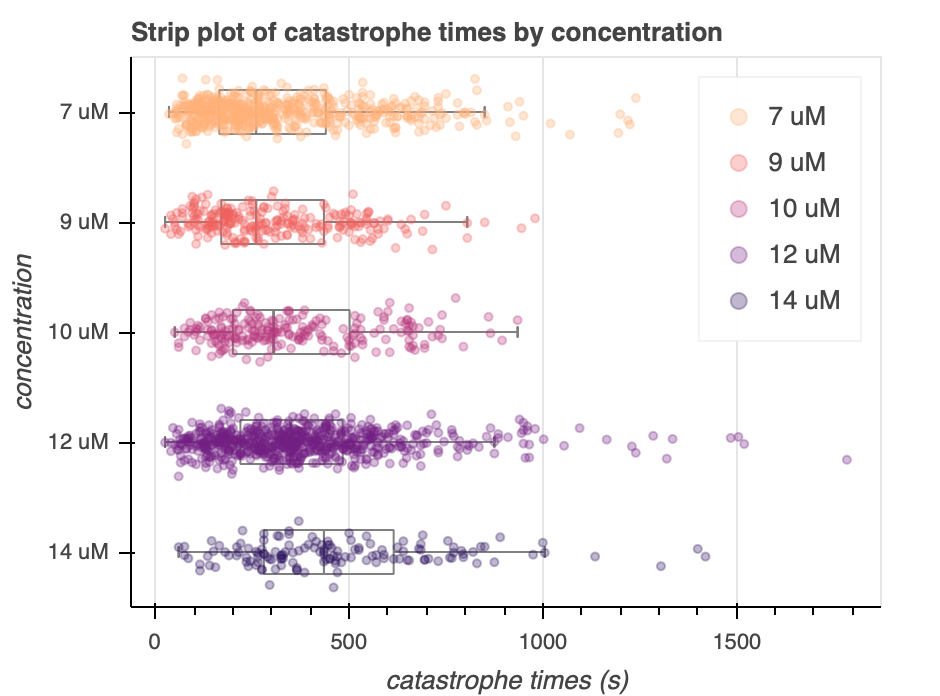

We can clearly see that the median catastrophe times increase with concentration. We can also see the bimodal peaks for $9\mu M$ and $10\mu M$. Notably, this plot also suggests that the number of data points for each concentration is different––there appear to be much more samples for $12 \mu M$ compared to $14 \mu M$.

Now, we can start doing some model comparison to see whether the gamma or two-event story is better matched to our data. As a reminder, the gamma distribution is parametrized by $\alpha$, the number of arrivals, and $\beta$, the rate of arrival. The standard catastrophe time is given by $\frac{\alpha}{\beta}$, so we would expect to see either increased $\alpha$, decreased $\beta$, or a combination of both, as the concentration increases. The two event story is parametrized by $\beta_1$ and $\beta_2$, where the MLE has $\beta_1 = \beta_2$. Thus, the standard catastrophe time is characterized by $\frac{2}{beta_1}$, and we would expect $\beta_1$ to decrease as the concentration increases. Let's start our model comparison by reminding ourselves of the MLEs our parameters, which we calculated previously. Table 1 can be generated using the viz_model_comparison.py module.

| 7 uM | 9 uM | 10 uM | 12 uM | 14 uM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alpha | 2.443910 | 2.679864 | 3.210835 | 2.915277 | 3.361502 |

| beta | 0.007550 | 0.008779 | 0.009030 | 0.007661 | 0.007175 |

| beta1 | 0.006179 | 0.006552 | 0.005625 | 0.005255 | 0.004269 |

| beta2 | 0.006179 | 0.006552 | 0.005625 | 0.005256 | 0.004269 |

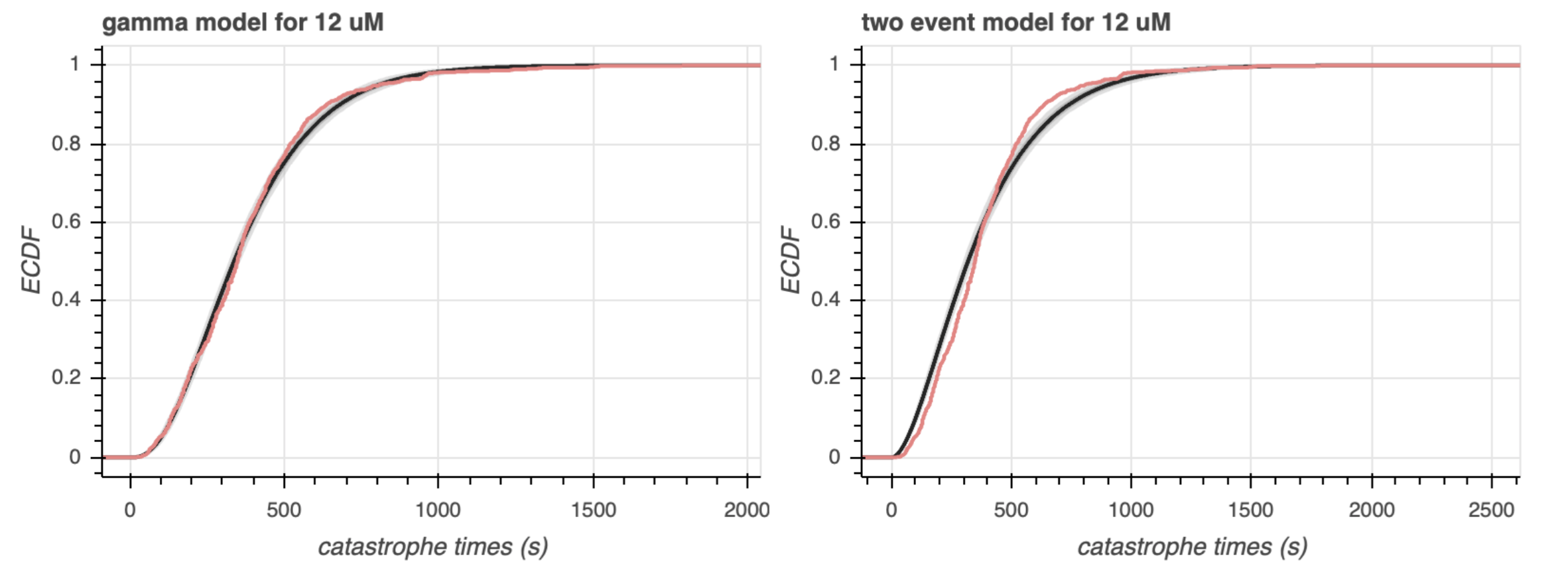

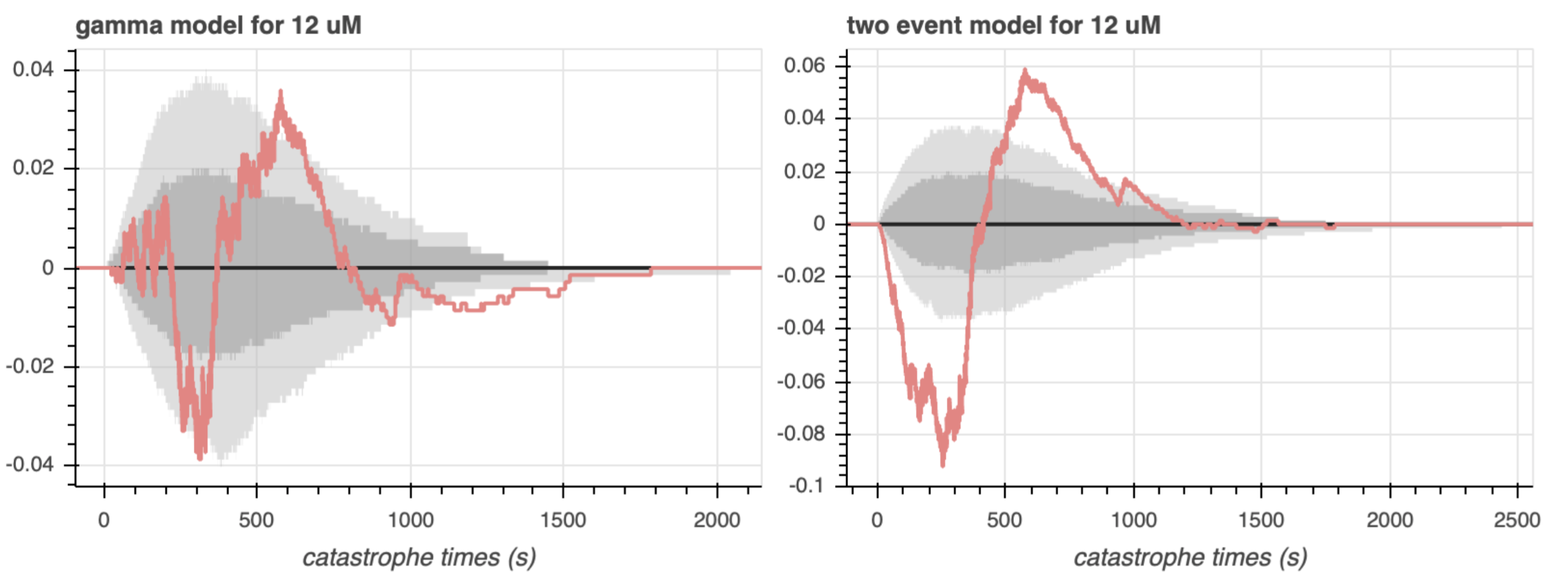

Now let's do some visual analysis. Using the viz_model_comparison.py script, we generate the plots of Figure 5. First, we examine a predictive ECDF (Figure 5a), where the coral line represents the ECDF of the observed data, and the gray line represents the predictive ECDF of the generative model. The $68$% and $95$% confidence intervals of the predictive ECDF are shaded in dark gray and light gray, respectively. The PNGs rendered below only show the distributions for $12 \mu M$ because the differences are more accentuated for $12 \mu M$. For a graphical comparison of all concentrations, please click on the HTML link underneath each PNG image.

For the gamma model, the observed data generally lie within the $95$% confidence interval of the predictive ECDF, although there are systematic deviations; for shorter catastrophe times (i.e. between $200$ and $400$ seconds), the model appears to underestimate the time, while for longer catastrophe times (i.e. between $400$ and $800$ seconds), the model appears to overestimate the time. We see the same trend with the two event model, although the mis-estimation is more egregious, with the observed data frequently falling outside of the $95$% confidence interval. For now, it seems like gamma model is winning out.

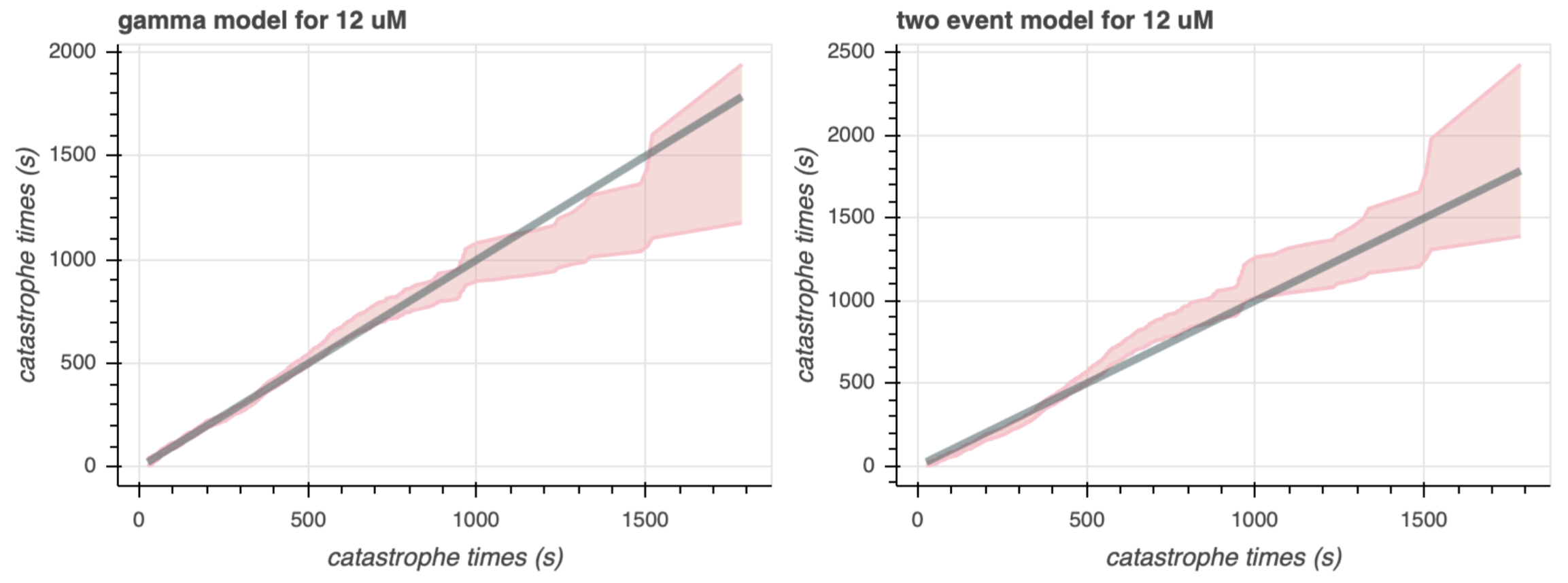

We can also look at a Q-Q plot of the observed catastrophe times and bootstrap sample catastrophe times from the generative distribution, as parametrized by the MLEs. This can be seen in Figure 5b. The catastrophe times from the generative model are plotted on the y-axis, and the observed catastrophe times are on the x-axis. The coral region shows the $95$% confidence interval for the quantiles, and the gray line represents the ideal plot, where the quantiles are the same between the observed the observed and model-generated data.

Interestingly, neither model looks particularly great at modeling the entire distribution of catastrophe times. However, we note that the gamma model appears to fit the data well for catastrophe times under $1000$ seconds, while the two event model veers out of the $95$% confidence interval (in both directions) under $1000$ seconds. Earlier in our exploratory data analysis, we saw that there are few catastrophe times over $1000$ seconds, and gamma's bad job at modeling for large catastrophe times may simply be due to less time points for those outliers. We are also primarily concerned with times below $1000$ seconds, because that is where we really see the concentration effects on the catastrophe time. Thus, the Q-Q plots also favor the gamma model at $12 \mu M$.

For our last graphical comparison, we plot the difference between the predictive ECDF and the observed data. The coral line represents the difference between the percentile of the observed data and the predictive ECDF, at a given catastrophe time. The dark gray and light gray regions represent the $68$% and $95$% confidence region of the predictive ECDF, respectively.

This visual is probably the most striking out of all three. For the two event model, the difference does not fall within the $95$% envelope of the predictive ECDF for values below $1000$ seconds, and there is a systematic bias for different values of catastrophe time. On the other hand, while there is also some systematic bias for the gamma model, the difference tends to fall within the $95$% confidence interval for times less than $1000$ seconds.

At this point, we're fairly convinced that the gamma model is the model of choice by just by looking at these graphical analyses. Nevertheless, let's confirm our belief using the Akaike information criterion. For a set of parameters $\theta$ with MLE $\theta^*$ and a model with log-likelihood $\ell(\theta;\text{data})$, the AIC is given by

\begin{align} \text{AIC} = -2\ell(\theta^*;\text{data}) + 2p, \end{align}where $p$ is the number of free parameters in a model. Recall that the AIC value can be very "loosely interpreted as an estimate of a quantity related to the distance between the true generative distribution and the model distribution," so a better model would have a lower AIC value. For both the gamma and two event distribution, we have two parameters, and we've actually already calculated the log likelihoods when we were trying to maximize it to get our MLEs for our parameters.

The Akaike weight of model $i$ in a collection of models is

\begin{align} w_i = \frac{\mathrm{e}^{-(\text{AIC}_i - \text{AIC}_\mathrm{max})/2}}{\sum_j\mathrm{e}^{-(\text{AIC}_j - \text{AIC}_\mathrm{max})/2}}. \end{align}Since we are taking the negative exponent of the AIC value, the model with the greater AIC weight is the better model, with $1$ being the sum of all weights. We display the MLEs, log likelihoods, AIC values, and AIC weights in Table 2. Note that we are displaying this across all concentrations, rather than just for $12 \mu M$. This table can be generated using viz_concentration_effects.py.

| 7 uM | 9 uM | 10 uM | 12 uM | 14 uM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alpha | 2.443910 | 2.679864 | 3.210835 | 2.915277 | 3.361502 |

| beta | 0.007550 | 0.008779 | 0.009030 | 0.007661 | 0.007175 |

| beta1 | 0.006179 | 0.006552 | 0.005625 | 0.005255 | 0.004269 |

| beta2 | 0.006179 | 0.006552 | 0.005625 | 0.005256 | 0.004269 |

| log_like_gamma | -4013.447639 | -1660.259101 | -1477.790621 | -4637.174646 | -966.632060 |

| log_like_two | -4074.742744 | -1691.190428 | -1513.546568 | -4731.428737 | -990.741370 |

| AIC_gamma | 8030.895278 | 3324.518203 | 2959.581241 | 9278.349291 | 1937.264119 |

| AIC_two | 8153.485487 | 3386.380857 | 3031.093137 | 9466.857475 | 1985.482740 |

| w_gamma | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| w_two | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

Wow, it looks like the gamma distribution is the unambiguous winner here, with the gamma distribution consistently having the lower AIC value and taking up almost the entire AIC weight, up to $6$ decimal places. Using both graphical and numerical analyses, we've found that the gamma distribution outperforms the two story model in modeling catastrophe times.

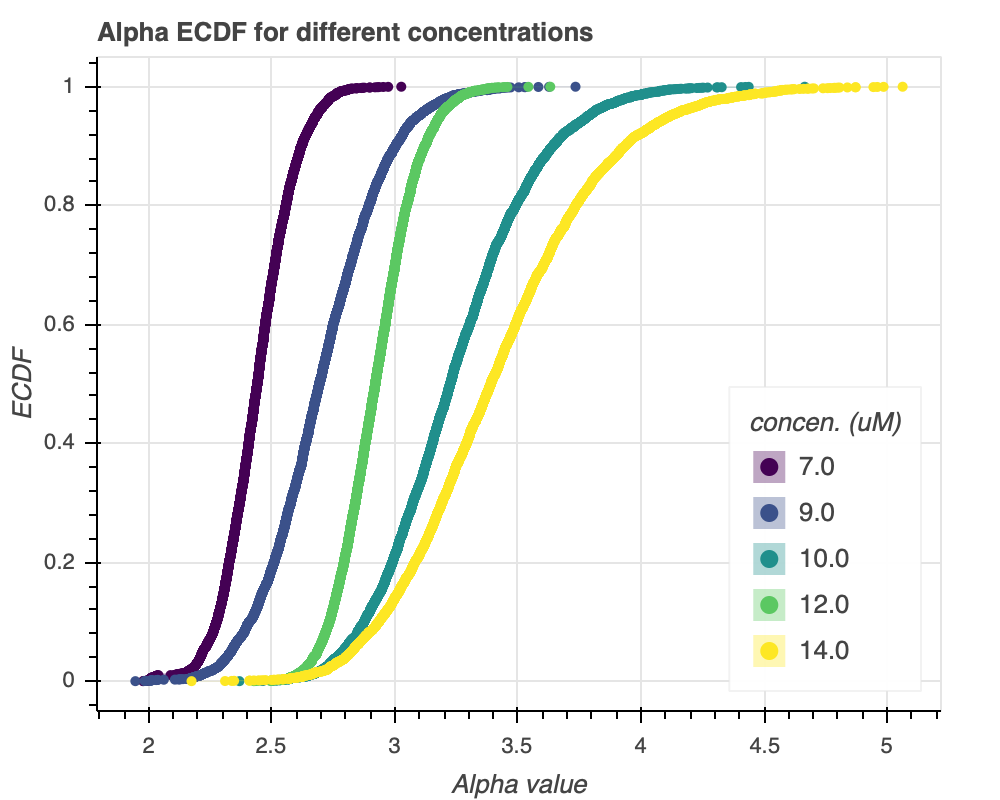

Moving on, let's see how the gamma parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ vary with concentration. Recall that the standard catastrophe time is given by $\frac{\alpha}{\beta}$, so we would expect to see either increased $\alpha$, decreased $\beta$, or a combination of both, as the concentration increases. For this analysis, we take bootstrap replicates of $\alpha$ and $\beta$ and look at the ECDFs and confidence regions of these parameters. The script to generate Figure 6 can be found in the viz_concentration_effects.py module. We start with Figure 6a, an ECDF of $\alpha$.

Of note, the confidence intervals are actually plotted as well, but since we drew enough bootstrap samples, they basically blend into a line. Generally, it appears that as the concentration increases, $\alpha$ increases as well. There is a reversal of this trend between $10 \mu M$ and $12 \mu M$, but it goes back with $14 \mu M$. This general trend suggests that microtubule catastrophe requires more "arrivals" as concentration increases. Before delving into the biological ramifications for this finding, let's look at the ECDF for $\beta$, the rate, in Figure 6b.

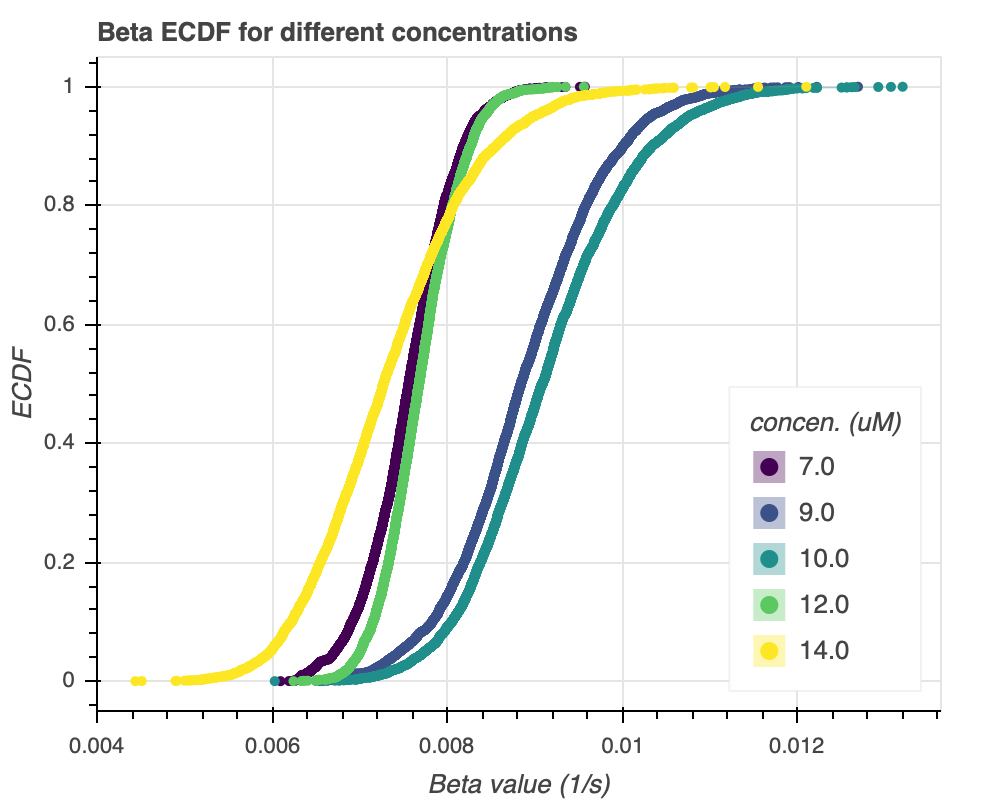

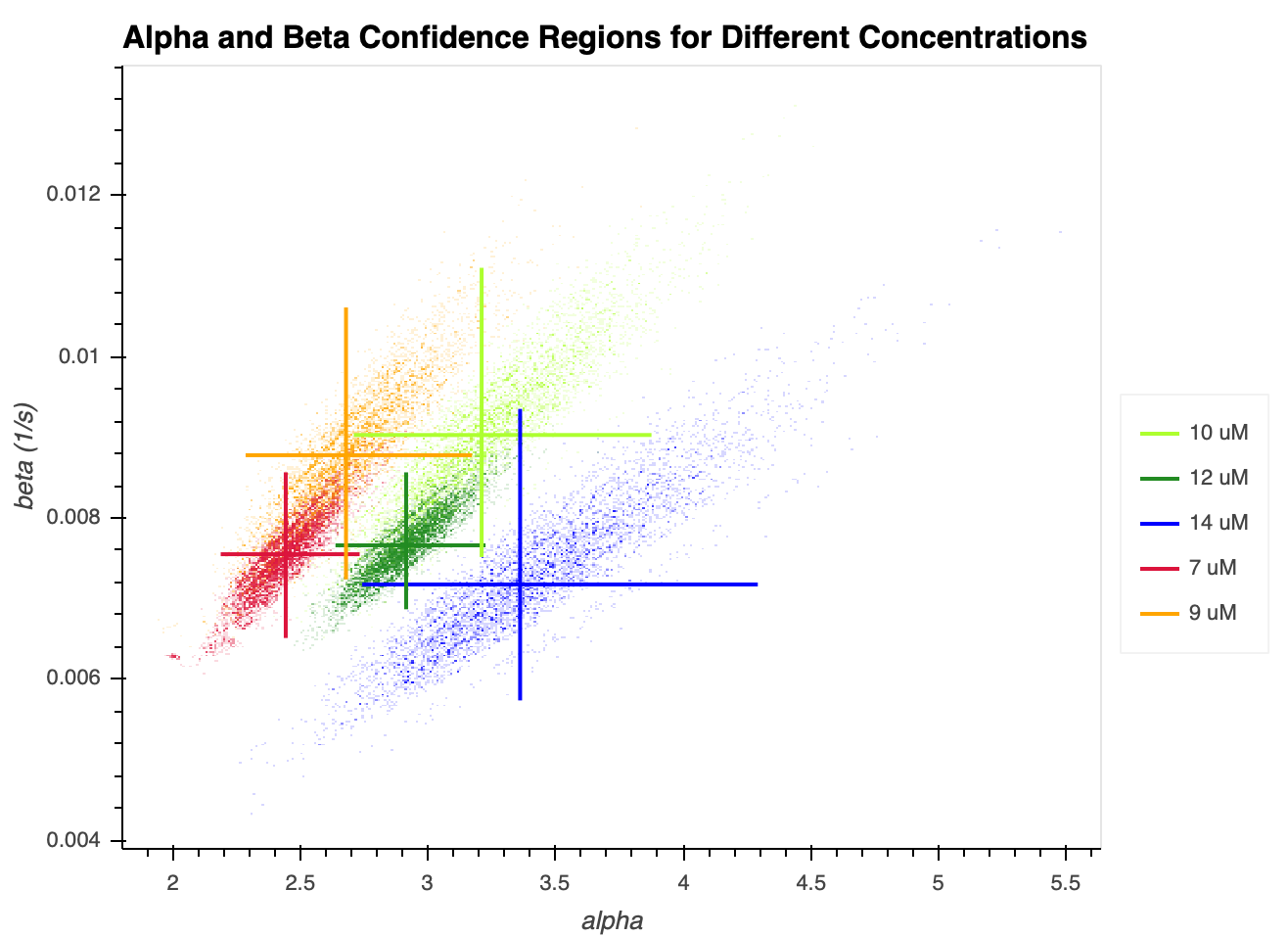

In general, there does not appear to be any noticeable trend between the concentrations for $\beta$. For concentrations $7$ to $10 \mu M$, it appears that $\beta$ increases, which is actually against our original expection. Nevertheless, this can be explained by looking at $\frac{\alpha}{\beta}$, the characteristic catastrophe time. Earlier, we saw that $\alpha$ increases from $7$ to $10 \mu M$, and we can think of it as "increasing too much" when it is being numerically optimized, and that it overshoots the observed catastrophe time. As a result, $\beta$ is numerically optimized to increase as well, to compensate for that overshot. This can be confirmed for concentrations $12 \mu M$ and $14 \mu M$, which both had relatively mild increases in $\alpha$ (or, in $12 \mu M$'s case, an actual decrease in $\alpha$). Thus, their $\beta$ values are lower. There doesn't seem to be much of a correlation that persists throughout the concentrations, though. We can also view the confidence regions of $\alpha$ and $\beta$ at the same time, for different concentrations in Figure 6c. The figure is plotted with datashading, and the segments represent the $95$% confidence intervals of $\beta$ and $\alpha$ on the y-axis and x-axis, respectively.

Here, we see that with the exception of $12 \mu M$, increased concentration increases the number of arrivals $\alpha$, and there is not a particularly noticeable trend in the $\beta$ arrival rates. Indeed, the confidence intervals for $\beta$ all overlap, while there is less confidence interval overlap as concentrations increase, and there is practically no overlap between $7 \mu M$ and the higher concentrations. Given that microtubules polymerize faster at increased tubulin concentrations, the higher arrival rates may be indicative that more arrivals of biochemical processes are needed to catch up to the fast-growing microtubule, in order to initiate catastrophe. A possible interpretation is that the longer the microtubule is, the more events need to happen before catastrophe can happen, since catastrophe would need to catch up the length of the molecule.

To further explore how different values of $\alpha$ and $\beta$ affect the gamma distribution, and how this looks overlayed on the observed data, we have created a dashboard, which can be explored in the next section. Here is a PNG still image of the dashboard to get you excited. The green yellow line represents the gamma distribution, parametrized by the shown $\alpha$ and $\beta$ values.